to return to the African projects menu

click on the logo

to return to the gallery's (UK) website

click on the AUGUST art logo

|

to return to the African projects menu |

to return to the gallery's (UK) website |

|

|||

|

|

|

Quanta Gauld . Keiskamma Art Project . Mbali Khoza . Fabian Saptouw (SA artists) |

|

|

|

| Curatorial statement and some images: | |

|

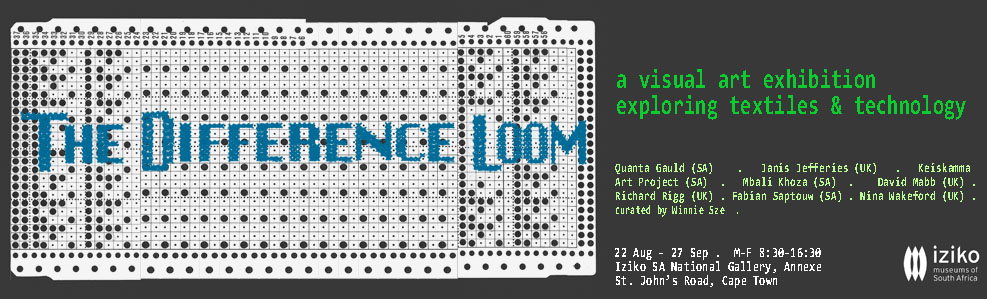

"The Difference Loom" is a visual contemporary art exhibition exploring textiles and technology. We sense the body in textiles, but not in technology. We discern the analytical in technology, but not in weavings. This exhibition is about those perceptions/disconnections, explored in that area where textiles and technology intersect, explored through the works by 8 artists who use textiles as one medium of social critique. |

|

At first the link between textiles and technology seems tenuous, but the first automated weaving loom and today's computer share a history. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| If there is an (extra) aura in hand-made art, do we also project something like it onto technology? | |||||||||||||||

|

Nina Wakeford explores this using the theories of seminal child psychologist David Winnicott as a platform in her work “Good Enough Mothers”. Winnicott theorises that an infant starts out in an internalized, idealized world but must transition to external reality for its proper psychological development. The role of the mother is to be initially the source material of the internal world, and then to help the child with its adaptation to the external; as such, the optimal mother is one who is just “good enough”. Wakeford wonders whether we are not “infants” still living in the internal idealized world with respect to technology? Consider old technology, such as dial-up phones, which we view with nostalgia and not as obsolete things, and our hubris that new technology will solve all our problems, while at the same time we fear being replaced by robots. Given the weight of this argument, one might be surprised by how “low-tech” a form is taken by Wakeford’s tie-dyed fabrics, bundled and set like figures on chairs. But perhaps they are our required “good enough mothers”? |

||||||||||||||

in the back: David Mabb (as before) in front: Nina Wakeford |

|||||||||||||||

|

Quanta Gauld’s practice investigates contemporary issues of human exploitation and abuse through writings on human morality, and tries to embody those words in her work. The exhibited piece is a response to Alan Paton’s novel “Cry, the beloved country”, from which the quote - and the work’s title - comes. Given that the wire fabric that Gauld has painstakingly woven is being unraveled by a machine, one might assume Gauld is criticizing the abuse of humans by machine. But as the machine was built and programmed by Gauld herself, it is as much her work as the weaving. So who then is the abuser? Perhaps both Wakeford’s and Gauld’s works remind us that technology is human-made, and therefore the achievements and limitations, the respect and abuses, are our own? |

||||||||||||||

| Quanta Gauld "A silence falls upon them all"; 2013; gold wire, arduino in wood box; dimensions variable |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| for more images, video clips and press clippings, please visit the exhibition on FB (link below) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| research consulted include the following: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

"A sound you can touch", Janis Jefferies, Montreal conference paper, August 2005 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||